More Than a Game: Understanding the Social Science of Sports

November 26, 2025 - Kelly Smith

What do sports reveal about society? More than most people realize.

What do sports reveal about society? More than most people realize.

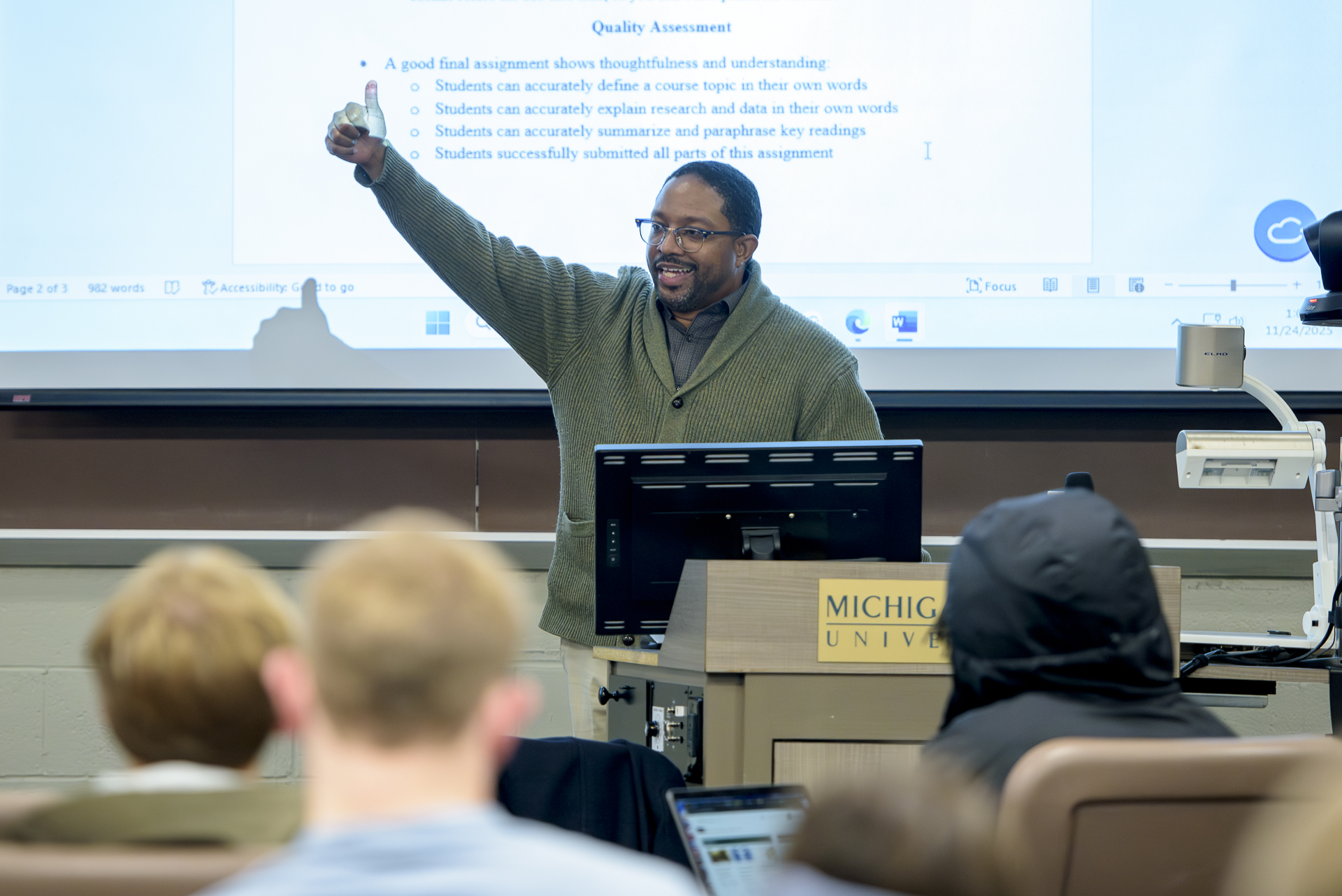

In ISS 328: The Social Science of Sports, MSU students are examining athletics as a cultural institution, exploring how issues of power, identity, and politics reveal the deeper forces that shape the world beyond the scoreboard. We spoke with Assistant Professor Bryan Ellis about the origins of the course, why sports are a powerful microcosm of society, and how critical thinking can transform the way we view “fun and games.”

What inspired the creation of this course?

In my youth, I was a student-athlete. I played basketball at the University of Montana. During my adolescence, I was a competitive track and field athlete. I was particularly good in the 800-meter dash. Also, my father was a high school basketball coach. That is to say that for most of my youth, I was passionate about sports, and I identified as an athlete.

When I decided to go to graduate school, in the first week of the semester, my research methodology professor wanted to know my research topic. I didn’t have one and had never thought about the question. After consulting with my mentor, he encouraged me to study sports. He also introduced me to the works of the pioneering sports sociologist, Harry Edwards, who was instrumental in the 1968 Mexico City Olympic protest.

With my decision to research and study sports, I found supportive faculty members in my program. Therefore, I wrote my MA thesis and Ph.D. dissertation on the subject. When I started teaching, one of my deans asked me to offer a unique seminar for a general education course for undergraduate students. Seven years ago, I designed a course on the critical study of sports—and I have been teaching it ever since.

What role does social science play in uncovering the deeper cultural, economic, or political forces behind sports?

I often tell students on the first day of class that if they don’t like sports, there is no reason to worry. Any lack of sports knowledge will not negatively affect their understanding or performance in the class. Students are shocked to find out that I am not a sports fanatic.

Studying sports is akin to the study of any institution in society. As sociologists can study family, education, corrections, poverty, and homelessness, we can also study sports as an institution of society. Essentially, we use the research and theoretical tools of the discipline of sociology to understand the social, cultural, and political patterns in the world of sports.

A central saw of the sub-specialty is the notion that “sports are a microcosm of society.” In other words, sports are not an aberration or different genera but are a part of the larger whole. This is the message I convey to students throughout the semester.

As an example, let’s take NIL (name, image, and likeness) deals in intercollegiate sports. Rather than think about NIL as an exclusive collegiate problem, I point out to students that the reason NIL emerged is not because the NCAA has changed its mind about its treatment of amateur student-athletes, but that NIL has come about as the result of a few lawsuits and NCAA settlements. In other words, the NCAA, as an American institution, was challenged by former student-athletes in the court of law. Because the verdicts were in favor of former student-athletes, the NCAA has had to make substantial changes to its guidelines and policies.

How does the course connect to current events or contemporary issues?

We begin our class by talking about Colin Kaepernick. I ask students if they think sports are political. I get a range of answers. While the Kaepernick movement happened in 2016, it still resonates with students today. It was probably the last sports movement that moved beyond the sports pages to make the front-page cover story. Since I talk about gender inequality and sports, I also discuss the sports controversy surrounding trans-athletes and sports competition, which is still unresolved today, and politically debated.

While I want the content to be relevant to contemporary conversations, I don’t want to over-emphasize news headlines and trends. I mostly bring up these subjects in the context of sports research and sociological theory—to show students how different concepts, theories, and research help us to understand these issues better. More than anything, I want students to stay curious and not fall into simplistic understandings of these topics that are rather complex and nuanced.

Sports as “the toy department of human affairs” is an interesting phrase. How do you challenge students to think beyond that idea in this course?

It is funny you bring that up. I love that phrase. I stole it from Harry Edwards, who I previously mentioned. If you were to ask the average athlete and sports fan, “How do you see sports?” I surmise that most of them would answer, "Sports are simply fun and games.” According to this view of “jockocracy,” sports are an escape from the real-world. This is what Harry Edwards meant. We don’t take the study of sports seriously.

I recall when I was working on my dissertation research at the Library of Congress, I sparked a conversation with another Ph.D. student who was there to work on her research. She was conducting research on the military and veterans. When she asked me about my studies, I felt embarrassed, like an impostor. I thought compared to her “serious topic” that my research was meaningless. When I responded to her question, she indicated that she didn’t know much about my topic. The Sociology of Sports is a rather niche sub-specialty in the field of Sociology.

As a former college basketball player (and now a University of Montana Hall of Famer!), how does your personal experience shape the way you teach this course?

It is an honor to be inducted into the Grizzlies Sports Hall of Fame as part of the 2025 class. I am even more proud because it was a team effort. I played on the 2006 men’s team that was inducted.

In the classroom, I recall my experiences playing sports to center the personal, so that the conversations aren’t remote and abstract. I also have students think about their experiences playing or watching sports. It is a delicate balance, because you are trying not to “toot your own horn” while drawing meaningful personal connections to the course material.

One of the strengths of the social sciences is that the content we cover is familiar and relatable since we all exist in society—and that is also one of the challenges, because we all bring our past experiences and deeply held beliefs into the classroom. Given the subject matter, we need not minimize and suppress the personal. It is an asset to teaching.

What do you hope students take away from this course? How does this course fit into the broader goals of the ISS curriculum?

I hope students learn to think critically and deeply about the way sports reflect our society, culture, and history. I hope that after students successfully pass my class, they will leave the notion that “sports are the toy department of human affairs” behind. I hope that if someone were to suggest to a student who has taken my class that sports are simply fun and games, that she would respond by saying, “I don’t know about that. I think it is a lot deeper.”

If you could describe the course in one sentence, what would it be?

Can I do one better and give you two sentences? Sports are not apolitical. Sports are a microcosm of society.

This is the third in a series about interesting ISS courses taught through MSU’s Center for Integrative Studies. Next up: The Pursuit of Happiness with Dr. Brandy Ellison, coming in December.